What slows cognitive decline in old age, increases earning potential throughout adulthood, and is best started in early childhood? Learning a second (or third!) language.

For decades, educators, researchers, and policy makers across the United States engaged in heated debates about how to ensure English proficiency. Some thought that learning two languages was somehow confusing to children and detrimental to their education. Far too often, debaters showed little regard for how a child’s home language tied him to his family, community, and culture.

Thanks to new research on the cognitive, social, and economic benefits of bilingualism, that debate has largely ended. Now we can focus our energy on supporting children whose first language is not English by building on their linguistic strengths—and on harnessing those strengths to help their peers who only speak English learn a second language too.

This issue of Young Children takes you inside several multilingual classrooms for in-depth, practical examples of how to enhance social, emotional, scientific, language, and literacy development with children who are learning more than one language.

Because a strong social and emotional foundation supports all other learning, we begin with “Paired Learning: Strategies for Enhancing Social Competence in Dual Language Classrooms,” by Iliana Alanís and María G. Arreguín-Anderson. The authors observed teachers in preschool through first grade Spanish-English dual language classrooms; based on their observations, they share detailed accounts of highly effective ways to help children learn to cooperate and collaborate. They emphasize learning in pairs as a way to create many low-pressure opportunities for dual language learners to engage in conversations.

Next, we step inside a dual language Head Start classroom where the teachers alternate the language of instruction (Spanish or English) weekly and offer multilingual supports throughout each day. Wanting to teach more science but not having enough time, the teachers join a professional development collaborative to learn how to incorporate science into their language and literacy activities. The impressive results are captured by Leanne M. Evans in “The Power of Science: Using Inquiry Thinking to Enhance Learning in a Dual Language Preschool Classroom.” As the teachers’ new lesson plans demonstrate, “science education offers [children] discovery-oriented play, vocabulary-rich content, and abundant opportunities to explore oral and written language.”

Although dual language models are a wonderful way to cultivate bilingualism—along with biliteracy, biculturalism, and a whole new lens on the world—they are not always feasible. Many classrooms are multilingual, so teachers are seeking ways to foster first-, second-, and even third-language development (along with progress in all other domains), even when they don’t speak all of the children’s first languages.

In “Five Tips for Engaging Multilingual Children in Conversation,” E. Brook Chapman de Sousa offers research-based and teacher-refined strategies to take on this challenge. With examples from a preschool in which over 30 languages are spoken, Chapman de Sousa demonstrates how children benefit when their teachers “use children’s home languages as a resource; pair conversations with joint activities; coparticipate in activities; use small groups; and respond to children’s contributions.” Active listening and gesturing are key ways teachers can be responsive and communicate caring when they do not speak a child’s first language.

Cristina Gillanders and Lucinda Soltero-González help teachers craft a strengths-based instructional approach in “Discovering How Writing Works in Different Languages: Lessons from Dual Language Learners.” This article carefully examines children’s emergent writing, with examples from prekindergarten through first grade, asking teachers to consider how a child’s knowledge of and ideas about her first language impact her writing in her second language. Teachers can then build on what the children already know and support children’s progress in both languages.

We close the cluster with “Can We Talk? Creating Opportunities for Meaningful Academic Discussions with Multilingual Children,” by Mary E. Bolt, Carmen M. Rodriguez, Christopher J. Wagner, and C. Patrick Proctor. Teachers and researchers together develop a structured approach for building multilingual children’s academic vocabulary, knowledge, oral language skills, and writing as they extend an existing unit on ocean animals to create far more opportunities for meaningful conversations. The authors describe how they helped the children develop the social skills, like turn taking, that are necessary for authentic discussions.

While this cluster focuses on children whose first language is not English, all children benefit from the rich, intentional, language-building instruction described in these articles.

To feature it in Young Children, see the link at the bottom of the page or email [email protected] for details.

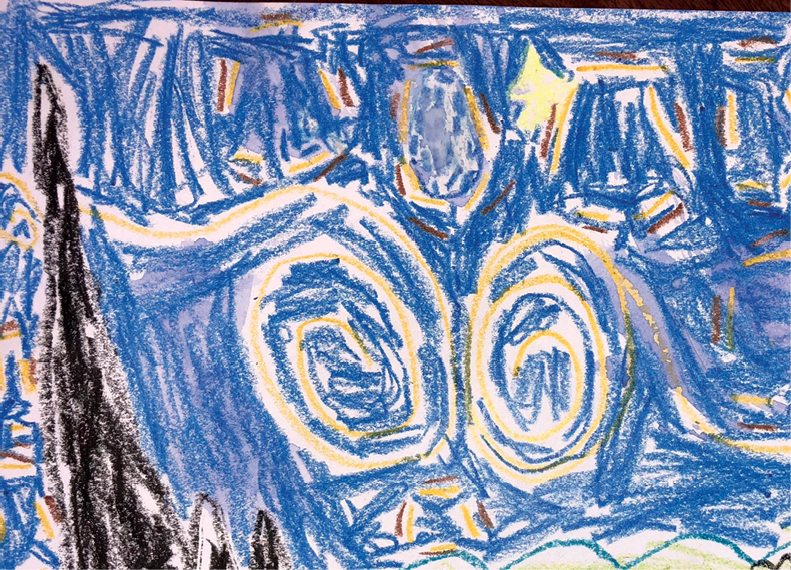

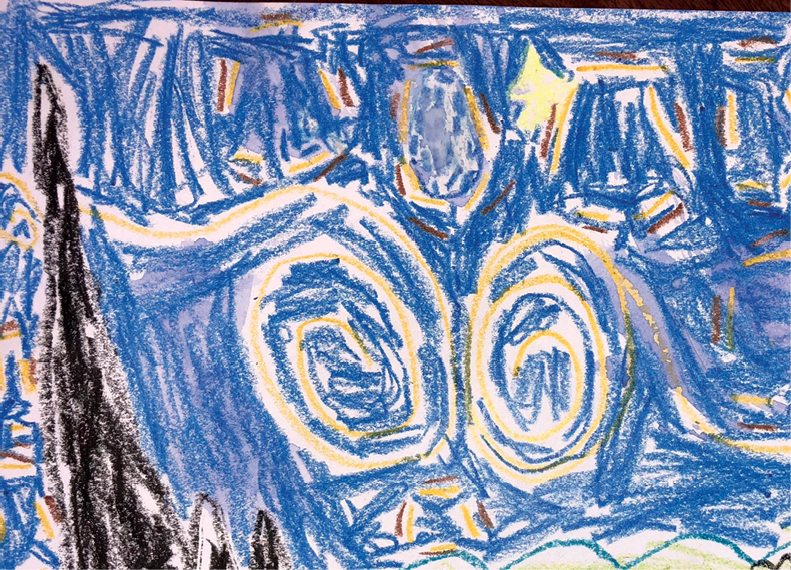

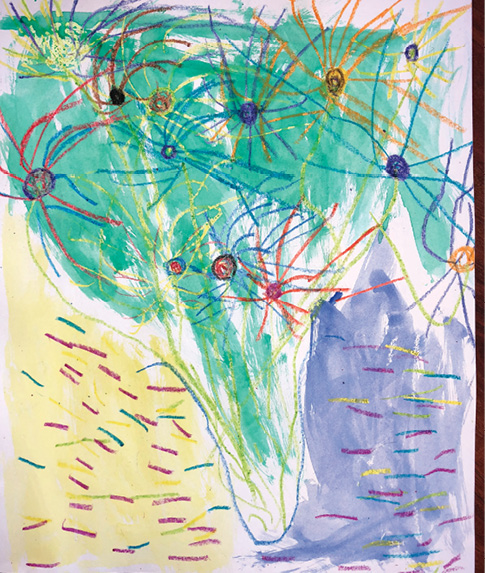

These masterpieces, inspired by van Gogh’s Starry Night and Sunflowers, were created by first and second graders in Ms. Bridget’s class at Plato Academy in Des Plaines, Illinois.

Send your thoughts on this issue, as well as topics you’d like to read about in future issues of Young Children, to [email protected] .